I’ve been frustrated lately with the quality and quantity of my work. I haven’t produced as much here at Get Rich Slowly as I would like — due largely to Fincon and its aftermath (calls and meetings, calls and meetings) — and what work I have produced isn’t as good as I would like. This lack of productivity makes me agitated, which makes me even less productive because I’m not in a good place mentally. It’s a vicious circle.

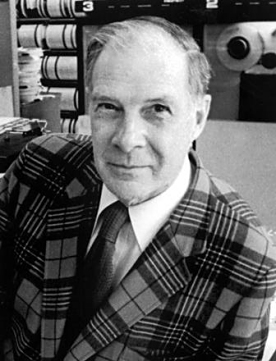

How nice, then, to rediscover the transcript of a 30-year-old talk from Richard Hamming, a former math and computer professor and researcher. (Hamming was also part of the team that worked on the Manhattan Project during World War Two.) Hamming titled his talk, which he presented on 07 March 1986, “You and Your Research,” but his actual subject was how to do great work.

How nice, then, to rediscover the transcript of a 30-year-old talk from Richard Hamming, a former math and computer professor and researcher. (Hamming was also part of the team that worked on the Manhattan Project during World War Two.) Hamming titled his talk, which he presented on 07 March 1986, “You and Your Research,” but his actual subject was how to do great work.

I re-read the transcript this morning while I was once more feeling exasperated with how little time I’ve had for writing lately. (For me, writing is my yardstick for productivity. It doesn’t matter how much other work I’ve been doing behind the scenes here; if I’m not publishing, I’m not happy.) Although this talk discusses the work of researchers and scientists, I believe that much of the advice applies to me and to writing. I suspect that many of you will find its lessons valuable too.

It’s a long talk, though. In order to make it more palatable — and in order to help me remember more of this material — I’m going to summarize Hamming’s message. I hope you find it useful.

What Greatness Isn’t

Most people think greatness is achieved by luck, Hamming says. They’re wrong.

Yes, great ideas and achievements all contain elements of chance, but hard work and preparation are the necessary groundwork to bring about this luck. “Luck favors the prepared mind,” Pasteur once said. And the brash Newton argued that, “If others would think as hard as I did, then they would get similar results.”

Hamming would agree that luck is no accident. Unexpected good things are more likely to happen when you do the work needed create favorable conditions for them.

Nor is greatness achieved solely by genius. Sure, there have been many brilliant scientists. But there’s been more great work done by folks who were less gifted yet willing to put in the time and effort to achieve the results.

Finally, it’s never too late to be great. Yes, many researchers did their best work when they were young. But plenty of others produced greatness later in life, after they’d had a chance to accumulate knowledge and experience.

So, if luck and youth and brains aren’t pre-requisites for great work, what is necessary? Let’s take a look.

How to Do Great Work

Among other things, Hamming says that great work requires:

- Courage. “Once you get your courage up and believe that you can do important problems, then you can,” Hamming says. “If you think you can’t, almost surely you are not going to.” To produce great work, you have to take risks. You have to be willing to think differently. You have to keep working even when things seem bleak.

- Adversity. “Ideal working conditions are very strange. The ones you want aren’t always the best ones for you,” says Hamming. He notes that when successful scientists get cushy labs and nice equipment, their productivity generally suffers rather than improves. “What most people think are the best working conditions, are not. Very clearly they are not because people are often most productive when working conditions are bad.” Necessity is the mother of invention, after all!

- Drive. “Knowledge and productivity are like compound interest,” Hamming says, making one of the most amazing points I’ve read all year. “Given two people of approximately the same ability and one person who works ten percent more than the other, the latter will more than twice outproduce the former. The more you know, the more you learn. The more you learn, the more you can do. The more you can do, the more the opportunity. It is very much like compound interest.” I want to print out this quote and post it prominently in my office.

- Open-mindedness. “Most people like to believe something is or is not true,” says Hamming. “Great scientists tolerate ambiguity very well. They believe the theory enough to go ahead; they doubt it enough to notice the errors and faults so they can step forward and create the new replacement theory. If you believe too much you’ll never notice the flaws. If you doubt too much you won’t get started. It requires a lovely balance.” Hamming also says that he’s noticed a difference between those who work with open office doors and those who work with closed doors. Those with closed doors seem to work harder, but they miss out on chance meetings that often lead to greatness.

- Importance. It’s not enough to do all these things if you’re working on something trivial. “If you do not work on an important problem, it’s unlikely you’ll do important work.” But what are important problems? Most of us think our work is important, after all. Hamming says it’s not the end goal, but how the problem is approached that makes work important. If you’re trying to solve world hunger, for instance, but using an unrealistic approach, then then the work is not important. Important work requires and important problem and and important solution.

- Iteration. Great work builds upon what has come before, both from yourself and others. “The essence of science is cumulative,” Hamming says. It’s iterative. “By changing a problem slightly you can often do great work rather than merely good work.” This happens frequently in the world of money writing. My colleagues and I are constantly building on what one or another of us has written. As a result, the ideas become more refined. They become greater.

- Communication. It’s not enough to do great work, Hamming says. You also have to sell it. What good is it to achieve something if you don’t let the world know what you’ve accomplished and why people should care. But, he says, this is tough for scientists: “Selling to a scientist is an awkward thing to do. It’s very ugly. You shouldn’t have to do it. The world is supposed to be waiting, and when you do something great, they should rush out and welcome it. But the fact is everyone is busy with their own work. You must present it so well that they will set aside what they are doing, look at what you’ve done, read it, and come back and say, ‘Yes, that was good.’”

It takes a lot of time and effort and discipline to produce great work. Is it worth it? Hamming believes it is. (So do I.) From his talk:

“Is the effort to be a great scientist worth it?” To answer this, you must ask people. When you get beyond their modesty, most people will say, “Yes, doing really first-class work, and knowing it, is as good as wine, women and song put together.” Or, if it’s a woman, she says, “It is as good as wine, men and song put together.”

“The value is in the struggle more than it is in the result,” Hamming says. “The struggle to make something of yourself seems to be worthwhile in itself. The success and fame are sort of dividends, in my opinion.”

Why People Fail to Do Great Work

For each person who does great work, there are countless folks who don’t. Many of those who fall short are talented, but something prevents them from achieving their full potential. But what? Hamming believes there are two fundamental weaknesses that hold people back.

First, they lack drive and commitment. “The people who do great work with less ability but who are committed to it, get more done that those who have great skill and dabble in it,” Hamming says. Talented people almost always produce good work, no matter how much effort they exert. But to produce great work, you have to put in substantial time and effort.

The second reason people fail to do great work stems from personality flaws. Hamming describes several of those he believes are most damaging, such as:

- An inability to delegate. Scientists who don’t delegate get less done. They think they can do better work than anyone else, so they insist on doing everything — even tasks that others could do for them. They don’t trust anyone else to take care of even trivial matters. (I’ll admit that this is one of my huge flaws. I know that I should focus my energy on the things that only I can do, but I haven’t learned how to pass things off yet.)

- Egotism. Scientists with big egos get less done. If you want to be a first-class person, you have to play the part. You can’t be a jerk. Being a jerk creates barriers where none need be present. Being agreeable and getting along with people goes a long way to spreading your message, which in turns helps others recognize the work you do.

- Senseless struggles. “Many a second-rate fellow gets caught up in some little twitting of the system, and carries it through to warfare,” Hamming writes. “The appearance of conforming gets you a long way…If you choose to assert your ego in any number of ways, you pay a small steady price throughout the whole of your professional career. And this, over a whole lifetime, adds up to an enormous amount of needless trouble.”

- Negativity. Lastly, Hamming cites a negative attitude as a barrier to greatness. Instead of complaining about things, he says, you should change your perspective. Look for ways something can be accomplished instead of reasons it can’t. Focus on your strengths (and the strengths of others) instead of on weaknesses.

Although Hamming’s talk was directed specifically at scientists, I believe his ideas are applicable to all work — even blogging.

This time through (my third time reading this), I was particularly struck by my own inability to delegate. You see, I want to do it all around here. But I can’t. Over the past year, that’s been a big barrier, one that’s been tough for me to overcome. It’s prevented me from attending to the matters that are most important — like writing.

Fortunately, I feel like I’ve finally surrendered to the fact that I need help. That’s why I’ve brought on board a partner to handle the business and technical side of things. My hope is that in the long term, this will give me much more time to write. My hope is that this will help me do great work!